Figurability of the ruin

Reconstruction and

re-signification of

Ancient Architecture

Of all the possible outcomes we can develop in the conservation of built heritage, the research question is whether it is preferable and advisable to encourage direct engagement with ruined architecture, in an exploration of spatiality understood as a rewriting of a substratum where reference elements for contemporaneity can be identified. Starting from Bergson’s philosophical reflections on the value of image and memory, the aim is to outline a best practice for the creative process, based on an analysis of the characteristics of Ancient Architecture. Covering, fencing, or merely traversing are design gestures that do not return an Ancient place to human activity but rather limit themselves to preserving and showcasing it. Interpretive reconstruction, on the other hand, does not claim an absolute truth but instead promotes a personal and dynamic experience of space, generating new memory to restore the sense of form and a lieu de mémoire.

Taking a step forward from international Charters, it is time to identify different approaches to the idea of reconstruction. In Burkhardt’s and Focillon’s postulations on the constant evolution of form, interconnected through analogical relationships, we can see how the reconstruction of form can become an opportunity to engage with what Aby Warburg called nachleben or engramma: elaborating stratified and anachronistic traces of historical complexities.

Reconstruction can be considered not only as a transformative intervention but as an opportunity to sculpt an accurate image of space. Thanks to the focus on traces and documentation, some projects seem to have succeeded in presenting an evocative image without being cryptic or freezing history and memory under protective shelters or screens. Memory is a function of the brain, but also a collective tool, enabling us to encode, store, and retrieve images and information from the past, thereby becoming a means to develop concrete actions on the territory.

The process I have attempted to summarize assigns memory a central role in projects situated in places heavily laden with history, aiming to connect the new, the projected, to the identity of the place sustained by our view of the past. To have memory means being aware of the processes that have shaped us as individuals and constructed the environment in which we move. The built landscape is one of the elements that defines our individual and collective identity, creating a network that assigns shared meanings to what we perceive. It is in the urban space that our collective memories are preserved. The depth of the built landscape, shaped over time, stands as a testimony to countless material and spiritual events.

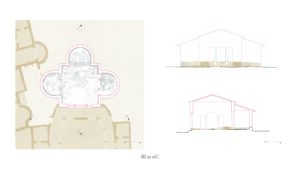

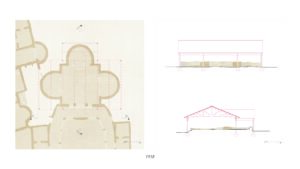

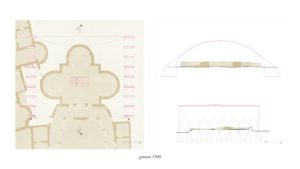

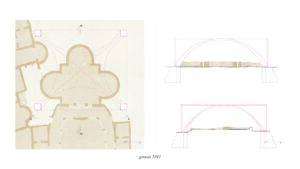

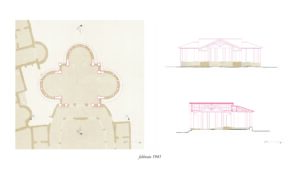

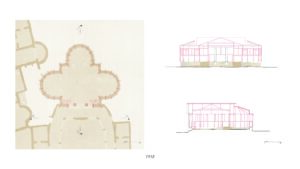

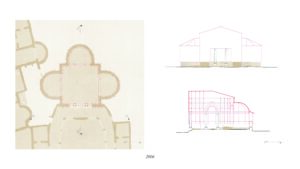

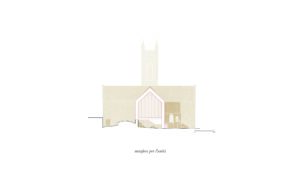

Retracing the stages that have shaped the image and fame of Villa del Casale in Piazza Armerina, we examine projects with clear narrative-spatial intentions, capable of attributing new meanings to the ruin. Ekphrastic projects, focusing on past architectures, represent the outcome of a fully analogical process. To structure these phases, the theory developed by Enzo Melandri in his philosophical and anthropological work becomes crucial, as it examines the various forms of analogy and their indispensable role in the different moments of the project.